Interstellar bottles, episode 3 : The fallen astronaut : exhibition on the moon!

Before Jeff Koons sent artworks to the Moon last February, Belgian artist Paul Van Hoeydonck was the only artist to have accomplished this feat. This incredible story, which unfolded in the 1970s, brings together Richard Nixon, a daring gallerist and a former golf champion...

On the evening of June 2, 1971, Van Hoeydonck ambled along Cocao Beach with a light step and a dreamy smile on his face. As he strolled the long stretch of concrete and sand bordered by the azure waters of the Florida coastline, somehow the Belgian artist knew that the dinner he was about to attend would change the course of his life. The dinner would take place in a restaurant frequented by visitors to the nearby Kennedy Space Center along with NASA employees working at the Cape Canaveral site.

Among the guests were astronaut David Scott, commander of the Apollo 15 mission scheduled to launch in eight days, and lunar module pilot Jim Irwin, accompanied by his wife Mary Ellen and their three children. During the lively dinner conversation, where they touched on archaeology and Mayan mythology, the lunar explorers told Van Hoeydonck that they admired his work. The artist felt confident to tell them more about a crazy project he’d been working on for some time that had piqued their interest: to be the first person in history to place a work of art on the surface of the Moon, at least officially (1).

How did the idea come about? At the time, Van Hoeydonck was a prominent figure on the New York art scene, having exhibited his work at New York City’s prestigious Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1961. This singular character, who had been a tobacco smuggler and an Esso gasoline salesman, was passionate about futurism and had devoted much of his work to the subject of space exploration.

In 1969, the director of the gallery that exhibited his work in Manhattan had the idea of placing one of the artist’s works on the Moon. Van Hoeydonck spent two years trying to convince NASA to no avail. Until he met the "messenger," a mysterious figure, allegedly a professional golfer before embarking on a career in space travel, who arranged the dinner with Scott and Irwin. After the meal, the two astronauts told President Richard Nixon about the project. "Is this artist a Democrat?" the frowning American president inquired. "No, he's Belgian." "Okay, we're good then," Nixon replied.

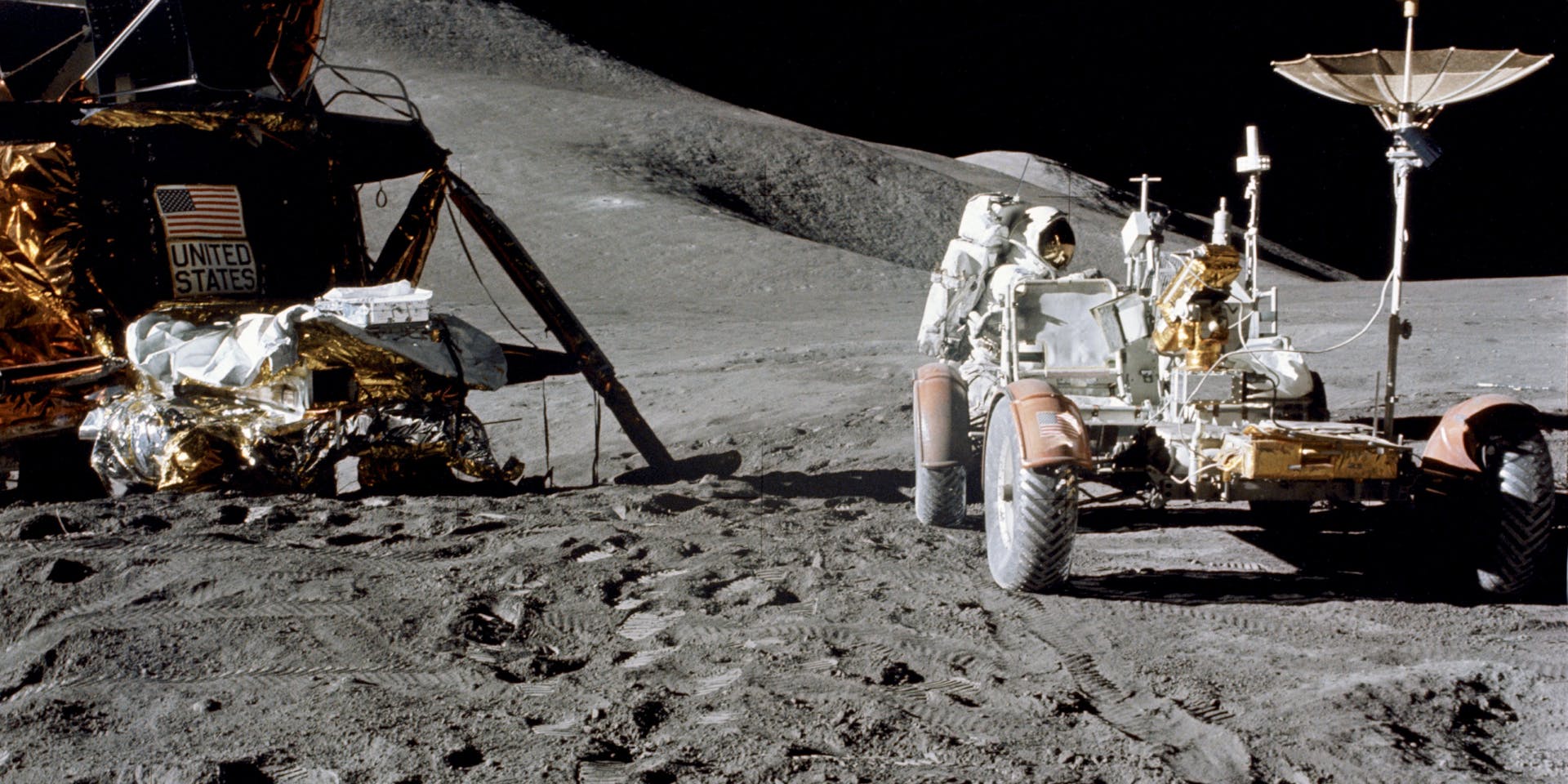

It happened on August 2, 1971 on the Apollo 15 mission. Commander David Scott, busy exploring the lunar surface, paused for a moment and retrieved Van Hoeydonck's creation, which he had secreted aboard in a pocket of his spacesuit. The diminutive 8.5-cm/3.3-inch figure, created with an unspecified gender and skin color to give it a universal character, was cast in aluminum to withstand the extreme temperature fluctuations on the Moon (-235° to 125° C/-390° to 260° F). Scott placed the object next to a memorial plaque bearing the names of eight American and six Soviet astronauts who gave their lives for the conquest of space. Lying on the fine lunar dust, the small metal figure became a miniature memorial called the Fallen Astronaut.

Though this was not Van Hoeydonck's original intention, his work, designed to stand upright and to symbolize hope, turned out to be the perfect commemoration.

But despite Van Hoeydonck's firm belief that this audacious undertaking would make him "as famous as Picasso," he did not receive the recognition he’s hoped for. His name was rarely mentioned by astronauts when they discussed Apollo 15. When it was mentioned, the Fallen Astronaut overshadowed Van Hoeydonck's rich body of work, which had been exhibited in museums around the world.

Paul Van Hoeydonck passed away on May 5, 2025, at the age of 99. Until the end of his life, he lived in Antwerp, where he kept painting... And never stopped looking up at the Moon.

(1) Une autre œuvre d’art, le Moon Museum, musée miniature imaginé par le sculpteur américain Forrest Myers, aurait été déposé sur la Lune en 1969, mais le projet était secret et il n’existe pas de preuve formelle.